Introduction

Have you studied the main classes of compounds in organic chemistry, but you just can’t understand the nomenclature? And, in particular, you don’t know how to name complex molecules where multiple functional groups are present?

Don’t worry, this is normal, because most organic chemistry books deal with nomenclature in separate compartments, that is, without a real connection between one class of compounds and another. This is done on purpose because dealing with the nomenclature in a unified way would be too complicated.

However, this book habit causes profound insecurity in students who will carry the problem of nomenclature further into their career.

Therefore, if you want to feel more comfortable with organic nomenclature and enhance your skills in this area, this article is for you.

In fact, below you will find a summary of the basic concepts for giving a name to any organic compound, following the systematic rules that we have tried to outline.

The concepts described here were taken directly from the 2013 International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) Blue Book. [1], [2] IUPAC is a commission of experts that has met several times over the years to publish guidelines for the correct nomenclature of chemical compounds. The Blue Book is related to organic chemistry, while other books identified by other colours are related to other branches of chemistry; for example the Red Book is for the nomenclature of inorganic compounds, while the purple one is dedicated to polymers and so on.

Without getting lost in further chatter, find out below how to give a name to any organic compound.

Types of nomenclatures

Nomenclature in organic chemistry is complicated by the presence of multiple ways of assigning names to compounds. In fact, the first names given to organic compounds were not linked to the structure of the molecule, but were assigned by chemists based on the imagination of the moment. Today some order has been brought about by IUPAC which has developed

the systematic nomenclature, i.e. an unequivocal nomenclature that provides the name of a compound by looking at its structure.

In this way, it will be possible to move from name to structure and from structure to name without misunderstandings.

However, even systematic nomenclature is complicated by the presence of multiple ways of naming structures; in fact, the so-called substitutive nomenclature can be combined with that of the functional classes. Alternatively, there may be common names that have been retained due to their overly prolonged use by chemists.

In our help, however, is the fact that the most used nomenclature is the substitutive one, so in this article we will focus on the latest one. While we will see the nomenclature of functional groups applied only to certain classes of substances such as ethers, esters and acid halides.

Would you like to read this article OFFLINE and have it for you? Download our article complete of Tables and Figures here.

Substitutive nomenclature

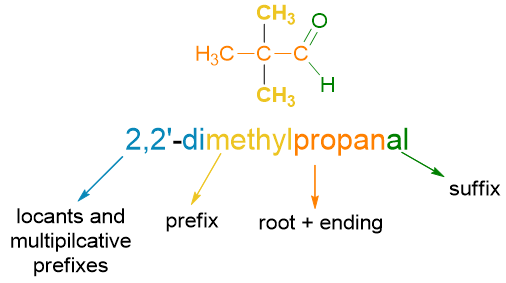

A name in any language is at least composed of a root, which provides information on the meaning and an ending, i.e. the final part of the word, which determines its plural or singular. Prefixes (before the root) or suffixes (after the root) can then be added to this base word to modify the basic meaning of the root (see scheme below, Scheme 1).

In organic chemistry, the name is built in a similar way. In fact, in the substitutive nomenclature the name is made up of:

– A root that refers to the parent structure. The parent structure is the part of the molecule that contains one or more carbon atoms bonded to hydrogens in an unbranched chain. Generally, the parent structure is given by the longest linear hydrocarbon chain present in the molecule; therefore, it usually refers to the number of carbon atoms present on the chain (e.g. met- et- prop- etc.). However, we will see later how to find the main structure;

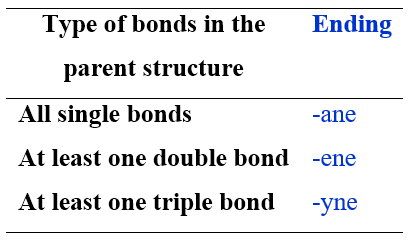

– An ending to be attached directly to the root and which indicates the unsaturation index of the parent structure. The endings are –ane to indicate a saturated backbone, –ene for the presence of a double bond, and –yne for the presence of a triple bond.

– A suffix indicating the characteristic functional group of the molecule. This group is easily found by consulting the seniority group tables; in fact, it corresponds to the group that is the most senior.

– A prefix indicating lower seniority substituents present on the parent structure.

– Locants, arabic numbers indicating the position of the substituents and unsaturation on the main chain. The numbers must be placed directly next to the part of the name to which they refer.

– Multiplicative prefixes, to be used when two or more identical fragments are repeated in the molecule.

You can see the structure of a name in organic chemistry being summarized in the following scheme (Scheme 2).

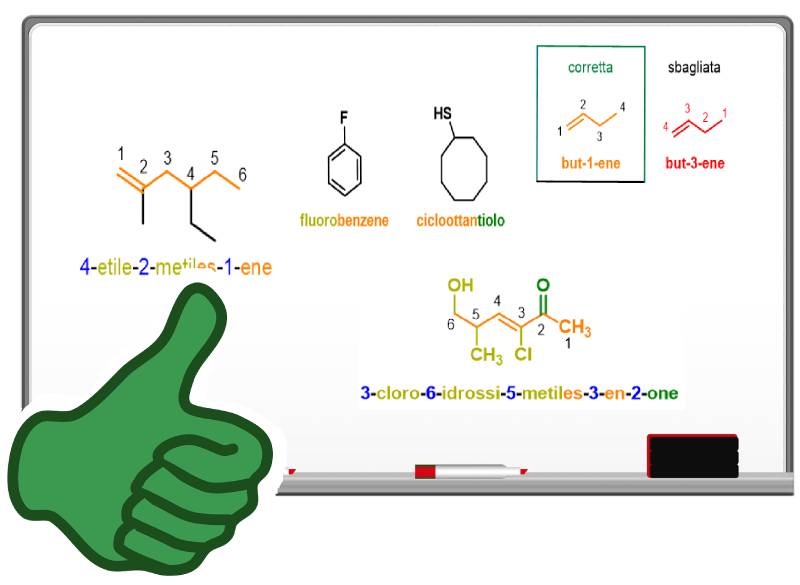

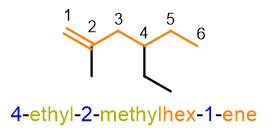

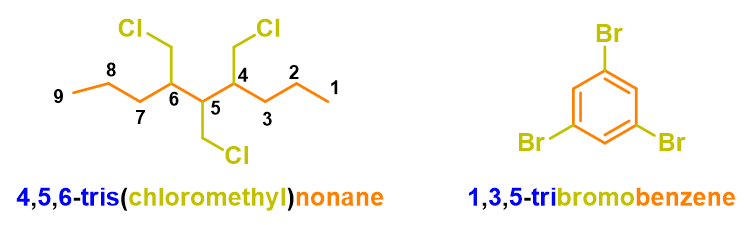

You can see an example of nomenclature of an organic compound in the example below.

If you don’t know how to get the name above, don’t worry because we will see it in the paragraphs below. For now, it is enough to know that the structure of a name in organic chemistry is made up of various blocks, like the carriages of a train; the main block, the locomotive carriage of our train, is that of the root which identifies the parent chain, which in the example above is prop-, namely 3 carbon atoms. In the following paragraphs, let’s see each of these blocks and how to put them together.

Root and endings

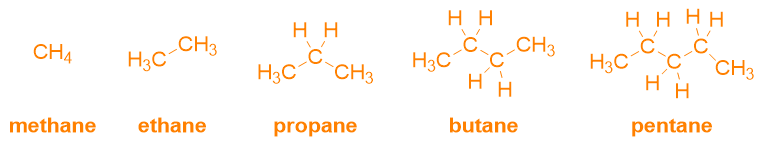

The root identifies the name of the parent chain and typically corresponds to the number of carbon atoms in the longest chain. In the following table, you can see the roots that are used to indicate a number of carbon atoms ranging from 1 to 100. The first four names, met- (1 C atom), et- (2 C atoms), prop- (3 C atoms), but- (4 C atoms) are common and therefore must be learned by heart. The remaining names, however, are derived from Greek numeral prefixes and therefore easily to remember (e.g. pent- indicates 5 carbon atoms, hex- 6 carbon atoms and so on).

The root is followed by the ending, which indicates the unsaturation index in the parent chain. The following table lists the endings to use depending on the bonds present in the molecule.

Names of Alkanes, Cycloalkanes, Alkenes and Alkynes

Alkanes are molecules characterized by the presence of a saturated main chain. As can be seen from Table 2, the presence of only single bonds is denoted with the ending –ane. Therefore, the name of alkanes is given simply by putting together the root, which indicates the number of carbon atoms present (Table 1), + the ending -ane. In fact, the first five alkanes will have the following names:

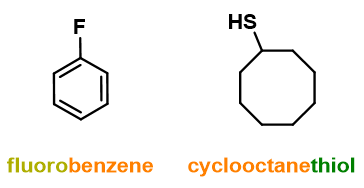

In the case of these simple molecules, the nomenclature is already concluded and there is no need to look for suffixes or prefixes, because these molecules do not contain other substituents or functional groups. So up to this point, you have already learned to name all the linear alkanes from 1 to 100. The good news is that you just need to add the prefix cyclo– to name the corresponding cycloalkanes as well (see the figure below for an example).

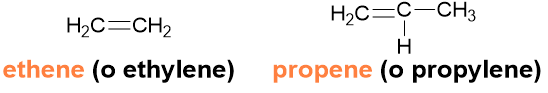

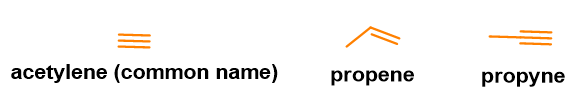

What happens to the nomenclature if there is a double bond on the main structure? You will simply need to use the ending –ene, rather than –ane, as seen in Table 2.

In the figure below (Figure 4), you can see the first two examples of molecules with double bonds, known as alkenes: ethene with two carbon atoms and propene with three carbon atoms. Both have common names still used today: ethylene and propylene.

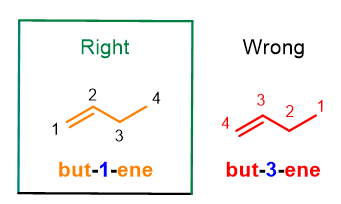

However, what happens for alkenes with a number of carbon atoms greater than 3? In this case, you will need to add an arabic number near the ending –ene to indicate the position of the double bond on the chain. To do this you will need to assign numbers to each carbon atom on the main chain in order to give the lowest number to the carbons with the double bond.

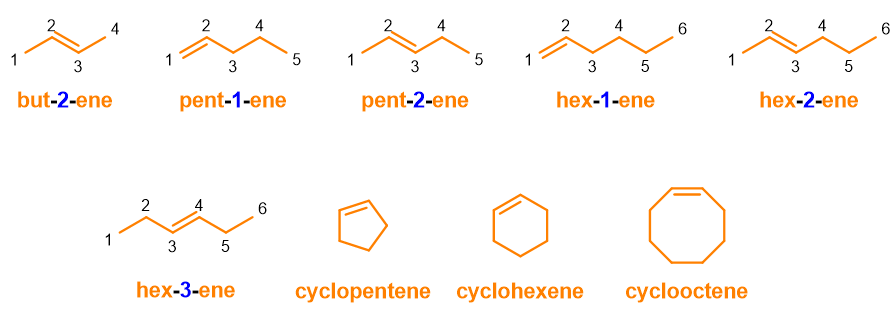

As you can see from Figure 5, but-1-ene is the correct nomenclature compared to but-3-ene, because the chain is numbered in such a way to give the double bond the lowest number. Furthermore, consider that the word 1-butene is no longer accepted by IUPAC, because the new instructions recommend to place the arabic number directly next to the term to which it refers. Other examples, you can use to practice, are below.

In figure 6 you can see how cycloalkenes, with only one double bond, do not need numbering; in fact, in this case, it would be superfluous to number the chain. However, IUPAC discourages omitting position numbers even when the numbering is logically superfluous, but in the case of cycloalkenes, the omission is accepted.

Know that you have now reached another stage: you have just learnt how to name alkenes too!

All we have to do is add the alkynes, i.e. the compounds with triple bonds. The construction of their name is identical to that of alkenes, except that it will be necessary to replace the ending –ene with –yne (Table 2): root + locant + yne. Some examples are depicted in Figure 7.

root names of aromatic compounds

The roots are not just the numbers of carbon atoms of the longest alkyl chain, as seen in Table 1, because the main structure is not always an alkyl chain. Therefore, the tables below collect the names of various compounds that can act as roots.

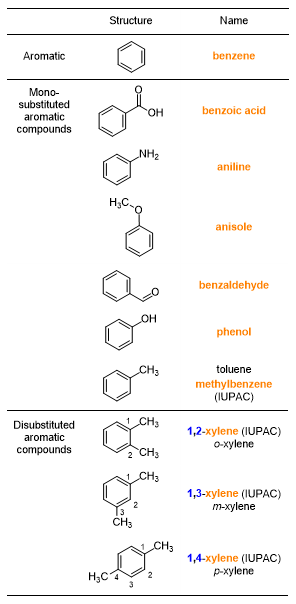

Let’s start by listing the names linked to the benzene molecule (Table 3). In some cases, Table 3 reports a double nomenclature: the common one and the IUPAC one. For example, toluene can also be called methylbenzene, which is the preferred IUPAC name. In the case of xylene, IUPAC recommends using arabic numerals to indicate the position of methyls, since the nomenclature ortho (o-), meta (m-), para (p-) is now considered obsolete. Xylene may also be called dimethylbenzene, however, the common term xylene has traditionally been retained.

Table 4, however, illustrates the typical names of some aromatic and partially aromatic polycyclic compounds.

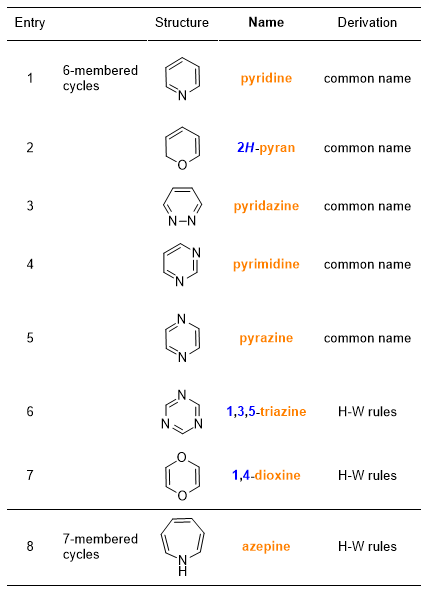

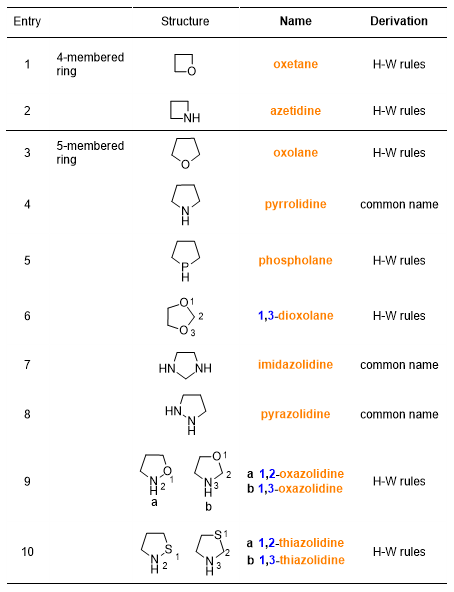

Root names of heterocyclic compounds

Let’s continue with the nomenclature of unsaturated heteromonocyclic compounds, which you can find in Table 5 and 6.

Then the saturated heteromonocyclic compounds, which you find in Table 7 and 8.

As regards heterocyclic compounds (Tables 5-8), there are some important considerations to do. Not all the names of these compounds are of common derivation, but most derive from precise rules adopted by IUPAC, when the common name of the compound is not too widespread. You can see in the last column of the Tables 5-8 whether the name of the compound comes from common names or from the Hantzsch-Widman (H-W) rules. But, what are these rules?

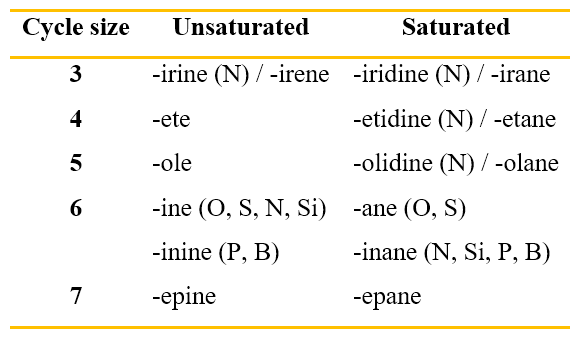

They are rules for naming monocycles containing heteroatoms. This system of rules is based on assigning names, ending with the letter ‘a’, to heteroatoms and giving priorities to them.

The following table (Table 9) lists just some of the names of the heteroatoms, starting from the highest seniority to the lowest one. Actually, it is not that difficult to remember the seniority of heteroatoms according to the H-W rules, because the highest seniority is given to the elements of group 17 of the Periodic Table (e.g. F is called fluora) followed by those of group 16 (e.g. O is called oxa), then 15 (e.g. N is called aza), then 14 and finally 13.

After giving the name to the heteroatom, the H-W rules require adding a suffix to the name of the heteroatom. The suffix indicates the size of the cycle and its saturation. Table 10 shows these names. Some of these names refer to a particular heteroatom; in that case, you will find in parentheses the atom to which the suffix refers.

In putting together the heteroatom name (Table 9) and the cycle name (Table 10), the final letter ‘a’ in the heteroatom name is lost.

Three examples follow (Figure 8). As you can see, the position of the heteroatoms must be indicated using the usual arabic numbers (locants) for the position. The lowest number is given to the heteroatom with the highest seniority, which will also be mentioned first.

Suffixes and prefixes

So far, we have seen what are the roots and endings and we have learnt that those last two are the main building blocks of an organic chemistry name. However, the real characteristic of the name is given by the suffix; the suffix gives the direction to our train. If, in fact, the root was the locomotive of our imaginary train, the suffix is the carriage of the train driver. It will give the direction to the entire machine.

Therefore, we are at the heart of our problem and the question that arises is: “How to find the suffix?”. Before finding it, however, let’s understand what it is:

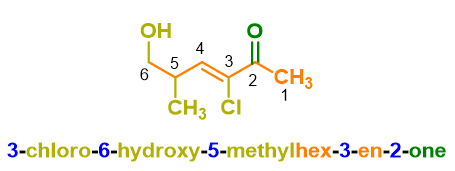

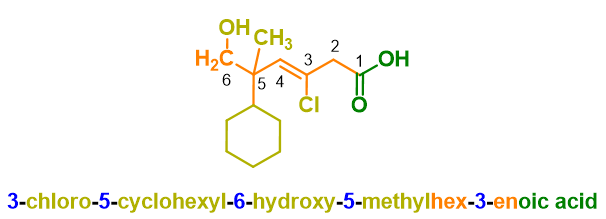

- The suffix is the part of the name to be inserted directly after the root and the ending; it refers to the main group characteristic of that molecule. The main group is the one with the highest seniority in the molecule.

So to find the main group within our structure simply consult the group seniority tables and see the suffix name for that group. In the table (Table 11) below, you can easily find the suffix to use. In this table, in fact, the various functional groups are ordered from the highest seniority group to the lowest seniority one. The same table also lists the prefixes. How come? The answer is simple: all those groups within the molecule that do not have the highest seniority will be named as prefixes and they have to be placed before the root.

You can see from the table above that in cases where the functional group has a carbon atom (for example in the case of carboxylic acids and its derivatives) this carbon atom can be considered “foreign” with respect to the parent chain and, in this case, the suffix will have the term carb– in it to indicate a carbon atom. For example, for carboxylic acid this suffix is –carboxylic, for the ester it is carboxylate, for nitrile it is –carbonitrile and so on. In the opposite case however, i.e. when the carbon atom of the characteristic functional group is considered an integral part of the parent chain, then you will have to use the suffix without the term carbo, as indicated in the table. For example, for carboxylic acid, the suffix becomes –oic preceded by the word acid.

Let’s take some examples to understand this point and how to take the first steps with Table 11, in general.

Molecule 1 in Figure 9 has the carboxylic acid as its highest senior group, which will therefore be the suffix; the amino group, however, having lower seniority, will act as a substituent (amino-). The root is the alkyl chain with 5 carbon atoms (pentane), the length also includes the carbon atom of the carboxylic acid, therefore the suffix will be indicated as (–oic acid). Furthermore, the chain numbering is done starting from the highest senior group, therefore the carboxylic acid, which the number 1 is assigned to. From the numbering, we also understand the position number to be assigned to the amine (5). Putting the pieces together, we get: 5–aminopentanoic acid.

Molecule 2 in Figure 9 is an example of a characteristic group not included in the parent chain. In fact, the parent chain in this case is the 6-membered cycle (cyclohexane), which will therefore be the root of the name. However, the carbon atom of the higher senior group (the carboxylic acid) is not included in the parent chain, so the suffix this time will be carboxylic acid (not –oic acid). The molecule also has a carbonyl group, which however, having lower seniority than the carboxylic acid, will be treated as a substituent (oxo). The numbering is done starting from the carboxylic acid and then passing through the ketone in order to give the functional groups the lowest possible number. Putting the pieces together, we get: 2–oxocyclohexanecarboxylic acid.

In example 3 in Figure 9, the reasoning is the same, except that, since the most senior group is an ester, it is necessary to indicate as the first element the substituent linked to the OR group of the ester, which in this case is ethyl. We will see very shortly the reason why it is called ethyl and not ethane.

Finally, in example 4, the most senior groups are the two ketones which will therefore be indicated with the suffix –one but preceded by the multiplicative prefix di-, to indicate the presence of two equal groups. The substituents on the parent chain (octane) are a hydroxyl group and a halogen; the two substituents are named in alphabetical order, so first bromo– and then hydroxy-.

As we have already mentioned, the prefixes indicating the substituents are not only those listed in Table 11, because other substituents are possible in organic chemistry, such as alkyl and halogen substituents.

These substituents are listed in Table 12 and are those substituents that are always of lower seniority and which therefore will always and only be identified as prefixes.

Among these substituents, there are the alkyl substituents, which are named with the same roots used for alkanes (meth-, eth-, prop-, etc.) but with the ending –yl, to indicate that it is a substituent. Similarly, for aryl substituents: they have the name of the starting compound but followed by the ending –yl (e.g. naphth+alene becomes naphth+yl). Benzene in this case has a particular substituent name and it is phenyl, this must be remembered by heart. Ethers are named with the usual root to indicate the number of carbon atoms (meth-, eth-, prop-, etc) followed by the term –oxy.

Other substituents are the sulfides, which are named like ethers, but followed by the term –sulfanyl, the halogens, named like the elements to which they refer, and the nitro group, called nitro.

Position numbers (locants) and multiplicative prefixes

All we have to do is looking at the last two terms used in organic nomenclature: position numbers and multiplicative prefixes.

We have already partially seen the former; they are the arabic numbers that indicate the position of the substituents and unsaturations. They are assigned by giving the lowest number to the group with the highest seniority and subsequently giving the lowest number to the substituents present. These numbers are separated from each other using commas (e.g. 1,2) and separated from the name using hyphens (e.g. 2,3-dimethyloctane) and are placed directly next to the word they refer to (see examples below). An apostrophe is added when the same number is repeated (e.g. 2,2′-dimethylhexane).

IUPAC recommends writing locants even in cases where it would be superfluous and allows their omission only in a small number of cases:

- Acyclic carboxylic and dicarboxylic acids and all their derivatives (e.g. amides, esters etc.), Figure 11;

- Alkyl chains with a single carbon atom (e.g. CH3Cl chloromethane, CH2Cl2 dichloromethane);

- Monosubstituted two-carbon alkyl chains (e.g. CH3CH2OH ethanol);

- Monosubstituted cycles (see Figure 12);

- Unsubstituted alkenes and alkynes with 2 and 3 carbon atoms and unsubstituted cycloalkenes and cycloalkynes.

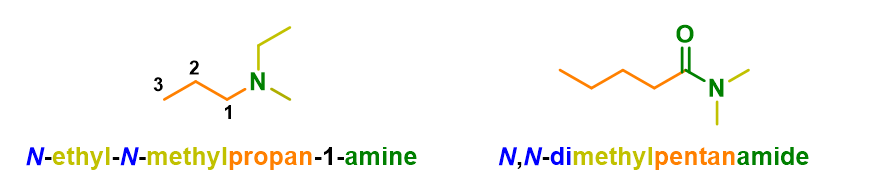

Regarding the use of locants, one last thing must be said: the exceptions to the use of position numbers are amines and amides; here, in fact, the substituents on the nitrogen are indicated with as many italic N letters as the substituents present on the nitrogen.

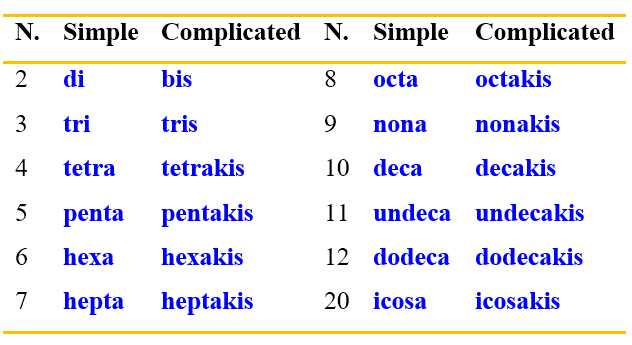

Now, the multiplicative prefixes remain to be clarified. These are prefixes to be used in the case of fragments that repeat within the molecule. The type of multiplicative prefix to use depends on the complexity of the fragment. For simple substituents the terms di-, tri, tetra- etc. are used, while for more complex fragments the corresponding bis-, tris-, tetrachis, etc. are used. The following table lists some of these prefixes.

To better understand how to use these prefixes, you can see the examples in Figure 15.

The rules for writing a name in organic chemistry

Summary and rules

Therefore, so far we have seen all the pieces that make up a name in organic chemistry. To recap we can take the train simile again; just as the train is made up of various carriages, so a name in organic chemistry is made up of various blocks:

- The root + ending which identify the parent chain (root) and the degree of unsaturation (ending). This is the locomotive carriage, because just as without it the train could not move, so without it our name would not exist at all.

- The suffix, the control car, the one where the pilot gives the direction and speed to the train. The suffix, in fact, gives direction to our name, because it tells us which group is most important in seniority on our molecule. In Table 11, we have listed these groups in order of decreasing seniority and given their suffix names.

- The prefixes, which give the name to the substituents, i.e. to all those groups, which have lower seniority after the characteristic functional group. There are two types of prefixes: a) the prefixes belonging to the most senior groups in Table 11 (the first class passenger carriage); b) the prefixes belonging to those functional groups that always and only act as substituents, listed in Table 12, (the carriage for economy class passengers).

- Locants and multiplicative prefixes to indicate the position and number of substituents respectively.

So given the composition of a name in organic chemistry, are there rules for putting the various pieces together with a certain criterion?

Of course, yes and those rules are listed below. Given a molecule to name:

- Determine immediately which is the characteristic functional group, seeing Table 11. The most senior group is the characteristic one, so write down its name separately as a suffix; if there are no functional groups, you can move directly to step 2.

- Determine the parent chain that is attached to the characteristic functional group. If there are no functional groups, the parent chain is the longest aliphatic one. Give it its name (root) and specify the degree of unsaturation by adding the ending –ane, -ene or –yne to the root. To find the root name, refer to Table 1 for aliphatic compounds and Tables 3–8 for aromatic compounds.

- Combine the name of the root + ending with that of the suffix.

- Identify the substituents (Tables 11–12) and put their prefixes in alphabetical order.

- Enter the multiplicative prefixes, if necessary, without changing the alphabetical order you have already given to the prefixes.

- Number the parent chain so that the most senior group has the lowest number and then the remaining substituents have the lower numbers. Then insert in the name the locants for substituents, unsaturations and main characteristic group where necessary.

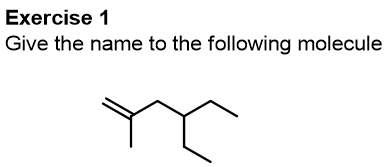

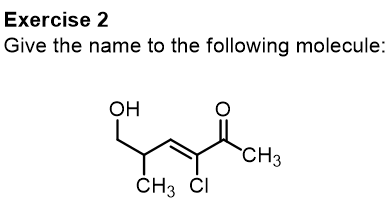

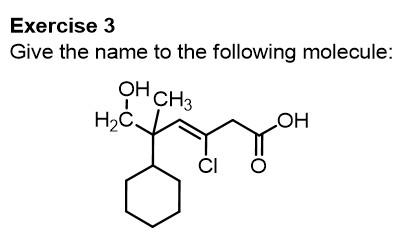

Done exercises

We conclude this part of the article relating to substitutive names by performing some exercises together.

Let’s start with this first molecule, try to give the name yourself and then check our explanation.

Nomenclature of functional groups

So far, we have seen the substitutive nomenclature, which is the most used one; in fact, with this nomenclature you can give a name to almost all organic compounds. However, there is also the nomenclature of functional groups, which is preferred only in the case of esters and acid halides. In fact, IUPAC encourages the use of the substitutive nomenclature also for all those other compounds for which the nomenclature of the functional groups is still widespread, i.e. ethers, ketones, sulfoxides, sulfides etc. This nomenclature consists of listing the names of the substituents in alphabetical order, followed by the name (separated by space) of the class to which that compound belongs. For example (CH3CH2)2O is called diethyl ether; ether is the name of the class, while ethyl refers to the two ethyl groups attached to the oxygen which are both treated as substituents, therefore with the same names (prefixes) seen for the substitutive nomenclature.

The name of the acid halides and esters is what we have actually already seen in Table 11, only that this nomenclature is not the substitutive one, but is the nomenclature of the functional groups. Therefore acid halides (RC(=O)-X) are named using the name of the halide (X) (chloride, bromide etc.) preceded by the name of the acyl group, which is the name of the R + –oyl or R group + carbonyl (if C=O is not part of the R chain). Similarly, esters, R’C(=O)OR, are named by first indicating the name of the R substituent, on the alcoholic part of the ester, and then using the name of the R’ + –oate or R’ + carboxylate group (if the C=O is not part of the R’ chain).

The following examples will clarify this nomenclature.

References

1) Favre, H., Powell, W. H., & Representation, S. (2014). Nomenclature of organic chemistry : IUPAC recommendations and preferred names 2013. In Royal Society of Chemistry eBooks. https://doi.org/10.1039/9781849733069.

2) Hellwich, K., Hartshorn, R. M., Yerin, A., Damhus, T., & Hutton, A. T. (2021). Brief Guide to the Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry (IUPAC Technical Report) [Dataset]. In IUPAC Standards Online. https://doi.org/10.1515/iupac.92.0027

This lesson

Organic Chemistry Nomenclature

€

6.50

Download as pdf (unchageable) file

Organic Chemistry Nomenclature

€

8.50

Downoald as docx (editable) file